This is a Black Men’s Health Column.

In the modern world, ‘Davids’ rarely triumph over ‘Goliaths’.

Still, I was heartened when former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores filed a class action lawsuit against the National Football League and three of its teams for racial discrimination in their hiring practices. One man taking on the world’s richest professional sports league.

It’s also why I’m fearful for Flores. What’s right and what’s fair don’t matter in the David and Goliath battles of today. The experience, evidence, and accolades that ‘Davids’ bring mean little in a battle where the victor is the one with more power and resources.

History is filled Black ‘Davids’ who look like Flores who not only lose, but suffer harsh penalties for daring to stand up – for their community, more opportunity, or simply their own dignity.

I am reminded of Civil Rights activists who dared to stand up, but were mercilessly crushed by racist power structures.

Make no mistake, what Flores is doing is critical, pushing for opportunities for people of color to get hired for senior-level NFL positions like head coach, general manager, offensive and defensive coordinator. In a league where over 70% of the players are Black, there remains a glaring lack of representation at those positions.

In over 100 years, the NFL has had 511 head coaches. Of that number, only 25 or 5% have been Black. Make that 26 if we count Mike McDaniel, who was hired to replace Flores as the Dolphins new head coach and classifies himself as biracial. Among the 32 NFL team owners, only two are persons of color: Jacksonville Jaguars owner Shad Khan, who is Pakistani-American, and Buffalo Bills co-owner Kim Pegula, who is Asian-American.

“This is where I’m going to make an impact for Black, and Brown, and women, and minorities, so that they’re not dealing with unfair practices and situations…,” said Flores in a recent interview on the I Am Athlete podcast show.

Flores also said he declined to sign a two-year separation agreement from the Dolphins, which would have paid him millions but also restrict him from suing the team and the NFL due to a non-disclosure agreement included with that contract.

Because of the lawsuit, Flores may never have another opportunity to become an NFL head coach again.

Yet, his fight recalls a similar one that took place over 50 years ago when a Black baseball player sued Major League Baseball because he did not want to be traded to a particular team.

In that fight, this ‘David’ lost but so many won because of him. His case helped transform the professional sports landscape as we know it. Tragically, he did not get to enjoy the fruits his case helped to cultivate.

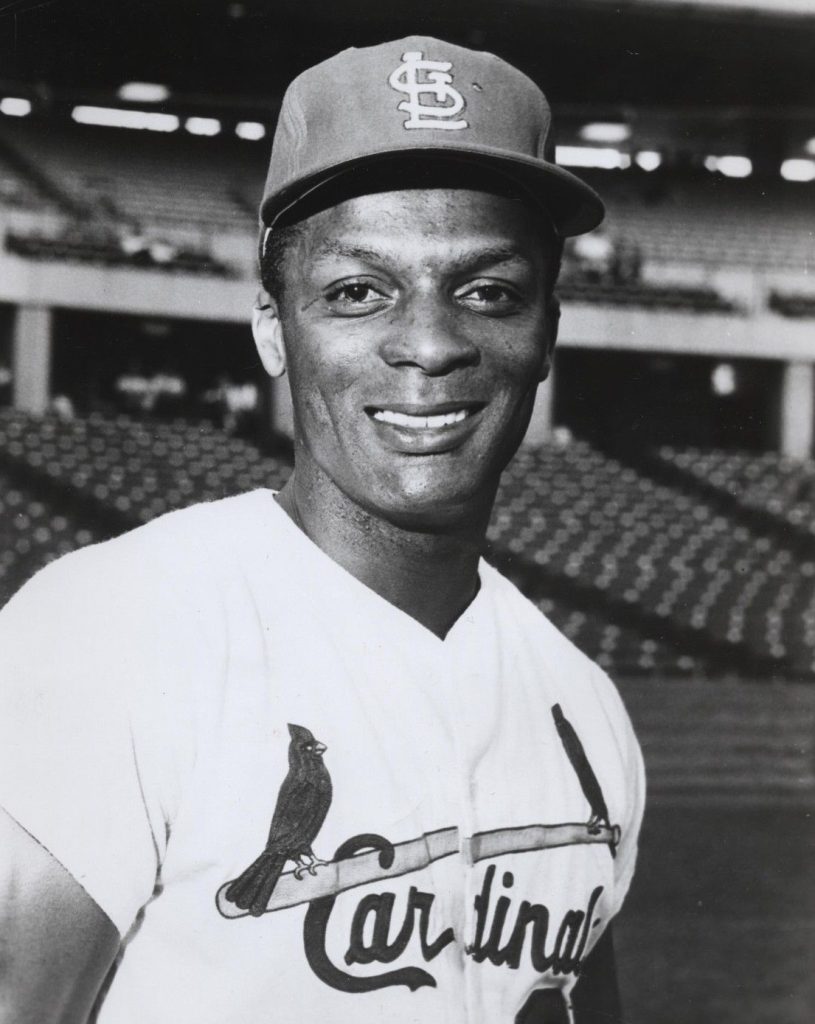

How Curt Flood Influenced the Entire Sports Landscape

Curt Flood wasn’t a star on the level of players like Henry Aaron or Willie Mays. However, he was a prolific hitter and perhaps one of the best defensive center fielders of his generation, as evidenced by the seven Gold Gloves he won over his career.

But Flood made one crucial mistake in the deciding game of the 1968 World Series: He dropped a routine fly ball in the fifth inning. That gaffe led to a two-run triple that helped the Detroit Tigers secure the championship.

Flood’s mistake snapped his error-less record at 568 total chances over 223 games. It also contributed to him being included in a seven-player trade to the Philadelphia Phillies a year later in 1969.

He refused to be traded, but there was nothing he could do about it.

At that time, all MLB players were contractually bound by a “reserve clause,” which prevented an athlete from changing teams or seeking his unconditional release. MLB owners had control of their lives, unilaterally deciding their pay and where they could play.

Flood eventually approached Marvin Miller, the then executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, about his case. Miller told him that “the odds were very much against him.”

Miller also told him that if he won, he would be blacklisted by team owners. No more opportunities to play or coach in baseball’s wealthiest league. No more opportunities to earn more wealth through the game he mastered.

“Curt, to his everlasting credit, said, ‘But would it benefit all the other players and future players?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘That’s good enough for me’,” Miller recalled in his autobiography “A Whole New Ballgame.”

A History-making Letter and the Supreme Court Case

Before taking the MLB to court, Flood wrote a letter to then MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn. It was his last stab at nullifying the trade and requesting to shop his services to other teams.

”After 12 years in the major leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes,” his letter, dated on Christmas Eve 1969, began.

“…I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.”

Writing that letter was a bold and extraordinary act. In fact, legendary New York Times columnist Robert Lipsyte referred to Flood’s note as the “preamble to sports’ version of the Emancipation Proclamation.”

In a 1998 column, Lipsyte wrote, “Those words seem quaint and mild now, but in a time when overt racial politics had just recently arrived in the sports world, they were as dramatic as the refusal of Rosa Parks to move to the back of a Montgomery bus.”

Nevertheless, Kuhn denied his request.

After that, Flood took the MLB to court and challenged the reserve clause as unlawful and that it violated antitrust laws. The players union provided financial backing for the suit.

He sat out the 1970 season, forgoing a $100,000 salary – high for a baseball player at that time.

“What I really want out of this thing is to give every ballplayer the chance to be a human being and take advantage of the fact that we live in a free and democratic society,” said Flood in a press conference. Controversially, he likened being a baseball player to being a slave – a well-compensated one no less.

The lawsuit lasted three weeks in Federal court before a ruling favored the owners. Flood’s team lost again in Appeals court, but the case eventually made it to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“Curt Flood’s legacy is that he gave his life for a whole lot of baseball players who don’t know who he is.”

Flood lost yet again by a 5-3 margin. Yet, he came “agonizingly close” to winning, as this Sports Illustrated piece reported.

A Supreme Court Justice recused himself because he owned stock in the Anheuser-Busch brewing company, which also owned the Cardinals, Flood’s team.

“That left eight men to rule, and they were split 4-4.” At the very end, there was a reversal that sealed Flood’s fate.

Chief Justice Warren Burger, who had sided with the player originally, switched his vote to avoid a deadlock. That made the final decision 5-3 in favor of Major League Baseball.

The Supreme Court ruled that the MLB’s antitrust exemption, which allowed the league to operate like a business monopoly, was an anomaly and not given to any other pro sport.

It would take several years, but Miller used that initial ruling to fight against the reserve clause. In 1976, when an arbitrator ruled that two MLB pitchers could become free agents, the reserve clause was killed. Players now had more autonomy.

But Flood’s case laid the groundwork to establish free agency in major professional sports, not just baseball.

What Flood Won and Lost

Flood did win, but personal and financial problems took their toll.

During the 1970 season, one of his biographers said that with no baseball to play, “drinking had come to dominate Flood’s life. He no longer had an incentive to remain sober each day.”

He eventually returned to play baseball for the Washington Senators in 1971 on a $110,000 salary. But that stint didn’t last long. Flood was out of shape when he arrived and left the team because he felt his performance wasn’t up to par. He lasted only 13 games that year.

The case made him a pariah among his fellow players and a target for racist and hateful fans.

Flood was accused of ruining the game. Fans slipped death threats into his car and threw beers at him when he was playing in the outfield. There was also talk in the baseball community that Flood pursued the case more out of self interest than out of magnanimity toward his fellow players.

He had little to no support from active players, his son Curt Jr. told The Atlantic.

“Jackie Robinson and Hank Greenberg were the only two connected with baseball who testified on his behalf. He was outgunned not only by the white power structure, but his own teammates and cats that he came up through the league with.”

When Flood left baseball, he did so quietly. The game he excelled at for most of his life not only scarred him, “It devoured him,” his widow told the Washington Post.

He left the U.S. for Spain, where he lived for five years and opened a bar.

In May 1981, a decade after his final baseball season, Flood was profiled by the Times as a man who had finally found contentment. He was back in his hometown of Oakland, California, where he served as the first commissioner of the Young America Baseball sandlot league for boys and girls.

He held down a Civil Service job and told the Times reporter he held no bitterness toward baseball players who were by then earning substantially more.

However, by 1995, his years of drinking and smoking had taken their toll. Flood was diagnosed with throat cancer.

Then on January 20, 1997, two days after his 59th birthday, he died of pneumonia at UCLA Medical Center.

Delivering the eulogy at Flood’s funeral, Rev. Jesse Jackson said, “Baseball didn’t change Curt Flood. Curt Flood changed baseball. He fought the good fight.”

Flood changed baseball indeed, but didn’t reap the rewards. The year he died baseball’s top salary was $10 million.

For what it’s worth, a photocopy of Flood’s letter to Kuhn and his autobiography is included in an exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. But Flood, the player, has yet to be inducted. He may very well never be, despite sacrificing his career and helping generations of athletes in the process.

In a New York Times short doc titled, “Curt Flood: The Athlete Who Made LeBron James Possible,” NBA legend Oscar Robertson summed up the man’s enduring contribution like this: “Curt Flood’s legacy is that he gave his life for a whole lot of baseball players who don’t know who he is.”

Brian Flores and a Hopeful Future

Brian Flores’s fight is different from Flood’s, but the same dynamic remains. That much was acknowledged by former NFL player Chad Ochocinco, one of the I Am Athlete co-hosts for Flores’s interview.

“I like what you’re doing with the lawsuit,” Ochocinco said to Flores. “I see it as somewhat David and Goliath in a sense — obviously the NFL Shield is extremely powerful.”

To which Flores quipped, “I got my slingshot right here.”

It may take months or even years for Flores’s case to be resolved, and even longer before we could see any lasting change.

When the NFL instituted its Rooney Rule in 2003, requiring teams to interview candidates of color for head coaching and senior operation vacancies, change was thought to be imminent.

Nineteen years later, the same problem exists: There are only three Black coaches in the NFL, counting McDaniel.

It must also be noted that since filing his suit, Flores was hired as a senior defensive assistant coach with the Steelers, a position far below his qualifications. But it’s an NFL job, nonetheless.

If Flores’s lawsuit is successful and brings about sustained, transformative change, my hope is that he can also reap the benefits, along with generations of future NFL head coaches, senior executives, and owners of color. Something Flood was never able to realize.

I also remain hopeful for a future where Flores will be held in high esteem, remembered and even honored for his contributions from his lawsuit.

That would be a proper David and Goliath ending.

Tacuma R. Roeback is a writer, journalist, editor and communications strategist originally from Brooklyn, New York. He is the Editor-in-Chief at Black Men’s Health.